In a recent study titled “Vascular channels formed by subpopulations of PECAM1+ melanoma cells”, published in Nature Communications, a team of researchers from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, have profiled a new subpopulation of melanoma cells in blood vessels of tumors.

In a recent study titled “Vascular channels formed by subpopulations of PECAM1+ melanoma cells”, published in Nature Communications, a team of researchers from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, have profiled a new subpopulation of melanoma cells in blood vessels of tumors.

These newly discovered cells, which imitate healthy endothelial cells normally lining tumor blood vessels may become a potential target for skin cancer therapies.

“For a long time the hope has been that anti-angiogenic therapies would starve tumors of the nutrients they need to thrive, but these drugs haven’t worked as well as we all had hoped,” Andrew C. Dudley, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, and senior author of the paper, said in a UNC news release. “There are likely several reasons why these drugs haven’t been effective; our research suggests that these previously uncharacterized cells could be one of the reasons.”

The majority of drugs developed to inhibit angiogenesis, or tumor blood vessels growth, are directed towards vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition, one of the key signaling pathways in endothelial cells that form tumor blood vessels. However, research has shown tumors can develop resistance against anti-angiogenic therapies.

With this problem in mind, the research team used a mouse model of melanoma, and treated it with an anti-angiogenic drug to block VEGF. Surprisingly, they found a new subpopulation of melanoma cells that was more prevalent in drug-resistant tumors and was completely insensitive to anti-VEGF therapy.

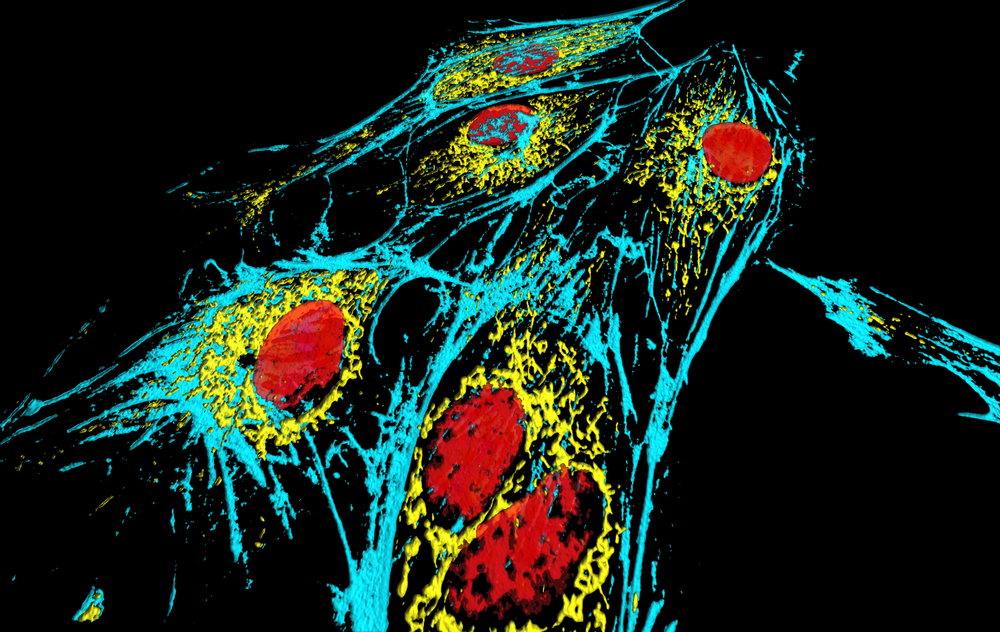

Dr. Dudley and his colleague James Dunleavey, isolated these endothelial cells from melanoma tumors, and after extensive genetic analysis, found these cells did not express the majority of biomarkers common to endothelial cells, including VEGF receptors.

“These cells looked very different from normal endothelial cells in cultures. We didn’t know what these cells were. For a while, we kind of scratched our heads until Jim conducted more experiments over the course of a year to find that these cells had several markers similar to melanoma cells,” Dr. Dudley added.

A more in-depth analysis revealed they were dealing with a new type of melanoma cell that expressed a protein called PECAM1, a key player in the function of endothelial cells.

“We don’t think these new melanoma cells are just passively filling in gaps between endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature,” Dr. Dudley explained. “How they come to form blood-filled channels seems to be an active process that involves PECAM1.”

Together with Paul Dayton, PhD, a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, and co-author on the study, the team showed that PECAM1-positive tumor blood vessels in mice had twice the vascular density of PECAM1-negative vessels. Furthermore, the blood volume of PECAM1-positive blood vessels was greater than PECAM1-negative vessels.

“We think these cells help allow tumor cells to interact in specific ways with bona fide endothelial cells.Anti-angiogenic therapies are typically used in conjunction with another drug. It could be that we’ll need to develop a combination of anti-angiogenic drugs to attack the endothelial cells that form blood vessels and the tumor cells that might form blood-filled channels in tumors”, Dunleavey concluded.