Researchers have identified a cellular pathway that regulates the ability of melanoma cells to migrate to other parts of the body. This newly discovered mechanism may lead to the development of new targeted therapies that prevent melanoma cells from spreading and form metastasis.

The study, “NFIB Mediates BRN2 Driven Melanoma Cell Migration and Invasion Through Regulation of EZH2 and MITF,” was published in EBioMedicine. It was conducted by researchers at the Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation of the Queensland University of Technology.

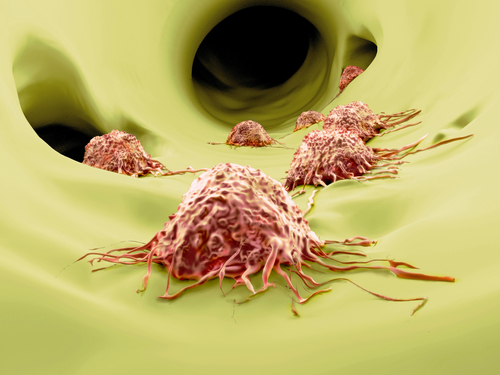

Cancer cells are not only characterized by their uncontrolled ability to grow and proliferate, but also by their ability to move away from the initial tumor site and invade other organs of the body (metastasis). In most cancers, the ability to metastasize is what makes them aggressive and difficult to treat.

Not all cancer cells are the same; some are more proliferative, while others are more invasive and migratory. Some cells can can even change between these two states, but little is known about the mechanisms regulating this switch.

“This is an important breakthrough as we have identified a ‘druggable’ target as part of this process. Preventing this switch to invasive behavior will enable us to prevent metastatic spread of melanoma and potentially other cancer types as well,” Aaron Smith, MD, senior author of the study, said in a press release.

Researchers found that two proteins, known as MITF and BRN2, were responsible for regulating the proliferative and invasive behaviors of melanoma cells.

With the use of laboratory models that mimic the tumor architecture and microenvironment of melanoma, the researchers showed that BRN2 activates an intermediate protein called NFIB that reduces the expression of MITF, blocking the proliferative activity of cancer cells and prompting them into the invasive state.

Additionally, NFIB indirectly promotes the expression of invasive genes, further supporting the metastatic capability of the tumor cells. This is done through the activity of EZH2, an enzyme involved in DNA modification processes. EZH2 inhibitors currently are being evaluated in a variety of tumor types.

“Once cells migrate away from the tumor we believe they no longer receive the signal that triggered the switch so the system resets to the MITF driven proliferation state which will then allow a new tumor to form at the new site,” Smith said.

Although the authors only described this mechanism in metastatic skin tumors, they believe this process also can explain the metastatic process for other types of cancers, but this requires further confirmation.

The study also suggests that drugs agains EZH2 that already are in clinical trials could be tested as a therapeutic strategy for melanoma.