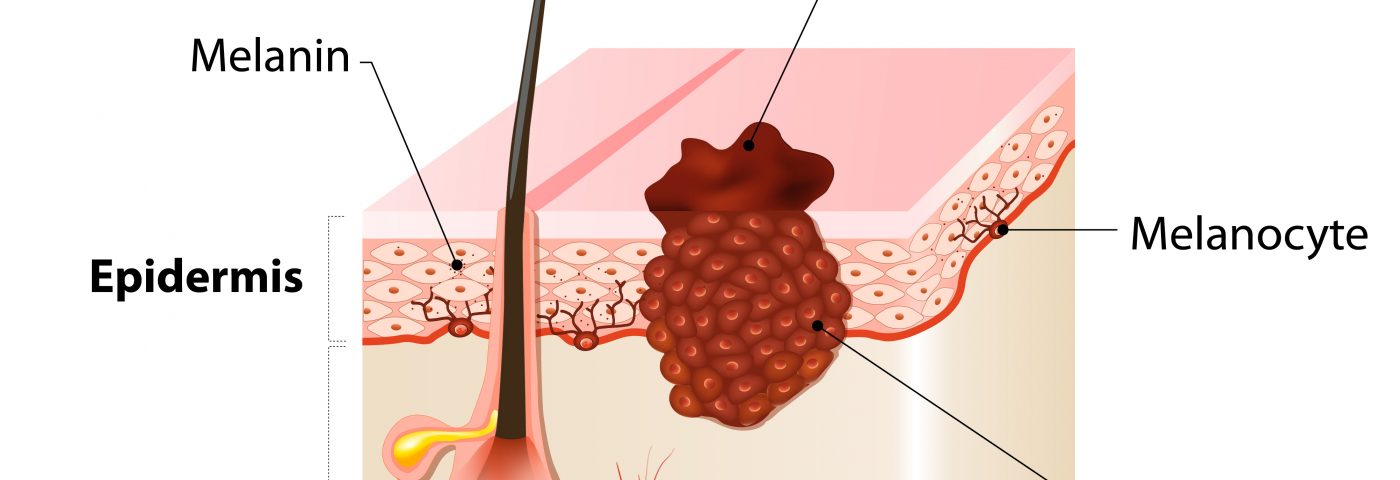

To reach circulation and invade other organs, melanoma cells must travel from the epidermis (outer layer of skin) where there is marked absence of blood vessels, to the dermis (deeper level of skin) where a vast network of blood vessels exists. Researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU) have revealed in a recent study that this process involves the production of tiny vesicles by the tumor cells that induce morphological and functional changes in the dermis — which in turn increase migration and proliferation of the melanoma cells.

Their study, “Melanoma miRNA trafficking controls tumour primary niche formation,” published in Nature Cell Biology, shows that certain chemicals can prevent the delivery of vesicles or the morphological changes which makes the chemicals promising drug candidates in preventing the spreading (metastatic) process of melanoma.

“The threat of melanoma is not in the initial tumor that appears on the skin, but rather in its metastasis — in the tumor cells sent off to colonize in vital organs like the brain, lungs, liver and bones,” Carmit Levy of the Department of Human Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry at TAU’s Sackler School of Medicine, and the study’s lead author, said in a press release. “We have discovered how the cancer spreads to distant organs and found ways to stop the process before the metastatic stage.”

Melanoma is known to form in the epidermis. But, for the tumor cells to reach other organs and form metastasis they first need to enter the into the blood that transports them to distant organs of the body. The researchers knew that first contact with the blood vessels was made in the dermis which is abundant in blood vessels, but how they reached that region of the skin was not known.

Researchers began to access how it happened by examining samples collected from early stage melanoma patients before the invasive tumor stage. They found that the dermis of the patients had morphological modification that had not been previously reported. They then set out to unravel what the changes were and how they related to the tumor spread.

“We found that even before the cancer itself invades the dermis, it sends out tiny vesicles containing molecules of microRNA,” Levy said. “These induce the morphological changes in the dermis in preparation for receiving and transporting the cancer cells. It then became clear to us that by blocking the vesicles, we might be able to stop the disease altogether.”

The researchers found two particular chemicals, called SB202190 andU0126, could block the release of those tiny vesicles or impair the morphological modifications in the dermis even after the arrival of the vesicles, respectively. These drugs may have promising therapeutic potential because they might impair the migration of melanoma cells towards the blood vessels and prevent them from colonizing other organs – the most threatening feature of melanoma.

The researchers believe that the presence of the vesicles or the changes in the dermis may be powerful markers for the diagnosis of early melanoma.

“Our study is an important step on the road to a full remedy for the deadliest skin cancer,” said Levy. “We hope that our findings will help turn melanoma into a nonthreatening, easily curable disease.”