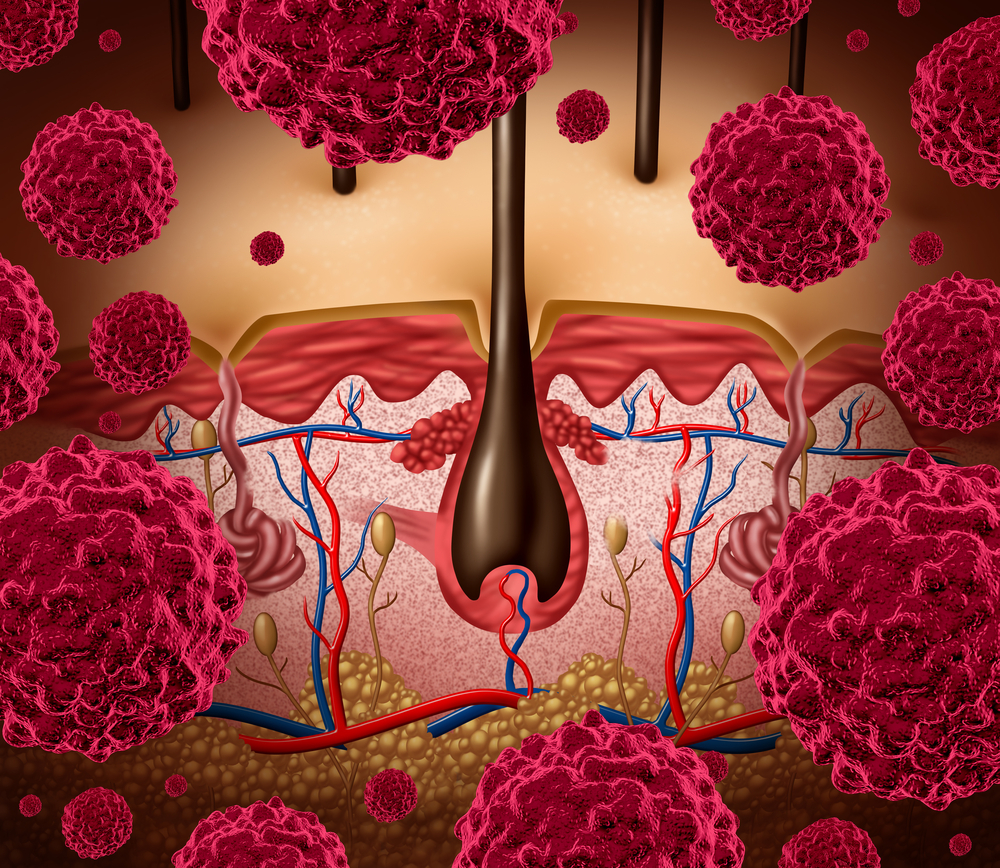

When melanoma is detected early, treatment can be highly successful. However, survival rates decrease significantly when cancer cells spread to the lymph nodes and other organs. In the last 5 years, targeted therapy and immunotherapy have emerged as very promising alternatives for patients with advanced melanoma. Even though these treatments offer a high potential, according to researchers, early detection is the best prognostic factor for an increased probability of survival.

When melanoma is detected early, treatment can be highly successful. However, survival rates decrease significantly when cancer cells spread to the lymph nodes and other organs. In the last 5 years, targeted therapy and immunotherapy have emerged as very promising alternatives for patients with advanced melanoma. Even though these treatments offer a high potential, according to researchers, early detection is the best prognostic factor for an increased probability of survival.

Recently, research has focused on the development of drugs that target BRAF mutations, a type of genetic defect that occurs in more than 50% of melanoma cases. According to Dr. Rhoda M. Alani, a skin cancer expert from Boston University School of Medicine, BRAF inhibitors “switch-off” tumor genes, inhibiting their proliferation and survival pathways, stopping their growth and decreasing tumor size.

Dr. Debjani Sahni, an expert in skin cancer and assistant professor of dermatology at Boston University School of Medicine noted in a press release that BRAF inhibitors are significantly effective in the beginning of treatment but unfortunately skin tumors eventually develop resistance to these drugs, finding ways to overcome pathway inhibition. The development of MEK inhibitors was the alternative found by researchers to overcome tumor resistance. Currently, BRAF and MEK inhibitors are administered together to provide more effective, longer-lasting therapy for advanced melanoma patients. Both drugs result in fewer side effects than either drug alone.

Dr. Alani notes that targeted treatment enables clinicians to provide patient-specific treatment, depending on the type of tumor. Currently, research is developing targeted treatments for melanomas not induced by BRAF mutations and occurring on places besides the skin, such as the eye. In the future, Dr. Sahni noted that the standard of care will most likely be the combination of 3 or 4 targeted drugs to improve the effectiveness of tumor therapy.

Tumor cells can evade the immune system by interfering with regulatory pathways that control the patient immune system. As Dr. Sahni mentioned, research has developed treatments to inhibit these mechanisms of regulation favoring more effective immune responses against tumors. However, immunotherapy is only effective in a small percentage of patients with advanced melanoma, normally producing a long-lasting remission state. Like targeted therapy, in the near future, clinicians may use a combination of various immunotherapy drugs to provide more effective treatments. Dr. Sahni said recent studies using this approach already have provided promising results.

Dr. Alani highlighted that in the future, clinicians will be able to decide earlier which melanoma patients have a higher risk of developing metastatic disease. This will allow clinicians to prescribe personalized treatments that can inhibit tumor metastasis and prevent recurrence.

Besides the development of targeted treatment and immunotherapies, an early diagnosis is still the best way to combat melanoma. If melanoma is treated before spreading to the lymph nodes or other organs, patients have a 5-year survival rate of 98% decreasing to 63% and 16% when the disease extends to the lymph nodes and other nearby organs or distant organs, respectively.

“Four years ago, we had nothing to improve advanced melanoma patients’ survival, and now we have several new therapies available, with several others in the pipeline,” said Dr. Sahni. “This is a really exciting time for melanoma therapy. We’re doing all we can to make a dent in this disease,” concluded Dr. Alani.